In this ongoing series, we ask SF/F authors to describe a specialty in their lives that has nothing (or very little) to do with writing. Join us as we discover what draws authors to their various hobbies, how they fit into their daily lives, and how and they inform the author’s literary identity!

When I was a kid, I used to think I didn’t like photography very much.

Then I went to Costa Rica, and realized that I just hadn’t spent much time in places worth photographing.

I still have the shots I took there. Most of them aren’t very good; when your previous photographic endeavors mostly involved tapping your camp friends on the shoulder and then snapping a surprise picture of them when they turned around, you don’t have much in the way of skill. And I did not bother about my skills as these HDR software options made things easy. But the sheer photogenic nature of some of the places I went came through despite my ignorance.

It was enough to encourage me. Over the next ten years or so, I began to pay attention to things like framing and composition, improving my photography through the basic decisions of where to stand and how much to zoom. The advent of digital cameras gave me the ability to see right away whether my shot had come out well, and the freedom to take a larger number of pictures meant I was more willing to just keep hitting the shutter button; my percentage of good images wasn’t any higher (in fact, it was probably lower), but sheer numbers meant I was getting more that were worthwhile. Slowly, bit by bit, my pictures got better.

But framing and composition can only get you so far… which is where my parents come in.

I always thought parents were supposed to steer their children away from drugs. Mine? Are a pair of pushers—my father especially. Years ago my brother and I bought my mother a photography course as a present; my father went along, and next thing you know, they’re both shutterbugs. Ever since then, they’ve been not-so-subtly encouraging my visual ambitions. In 2011, after I’d made enough noises about wanting a more advanced camera than your standard point-and-shoot, they gave me my mother’s old camera, a Leica V-Lux 2. It wasn’t quite a system camera—the sort where you change out lenses—but it offered me a lot more control over how I took the pictures. If you’ve ever paid attention to photography, you’ll have heard various arcane terms like “f-stop” and “ISO;” well, I finally knew what they meant, and how to employ them. Suddenly I could get pictures like this one:

Because at last I knew how to make my camera create a shallow depth of field, rather than relying on it to guess that I was trying to achieve that kind of effect. I could compensate for dim lighting, rather than winding up with grainy, horrible messes. I could keep bright shots from being blown out. Hooray!

But controlling the camera’s settings can only get you so far… which is where Lightroom comes in.

Despite having a growing interest in photography, I’d resisted doing any kind of editing on my digital pictures. I didn’t want to “photoshop” them, I insisted—I meant the term as a pejorative—and editing sounded like an awful lot of work, anyway. Despite the Drug Pusher Extraordinaire constantly encouraging me, I refused to do anything more than drop the images onto my computer and call it a day.

Until a year and a half after the Japan trip. My husband and I had been to Poland; I gave my father a thumb drive with a few of my shots and said, “Okay. Show me what Lightroom can do.”

Two minutes later I was hanging off his sleeve, begging for Lightroom as a Christmas present.

See, up until that point, I’d only understood about half of photography—the half that takes place before you press the shutter button. The process doesn’t end there, though; it never has. Back when we all took our pictures on film, there was this thing called “development,” and a skilled developer could do all kinds of things with the raw negative: crop, straighten, bring up the highlights here and deepen the shadows there, enhance color or mute it, etc. Refusing to edit my photos was a bit like refusing to develop the negatives—or rather, refusing to let anybody do anything more than run them blindly through a standard chemical bath (which is probably what happened at most photo-development places). If I wanted to be a good photographer, I had to start thinking about development.

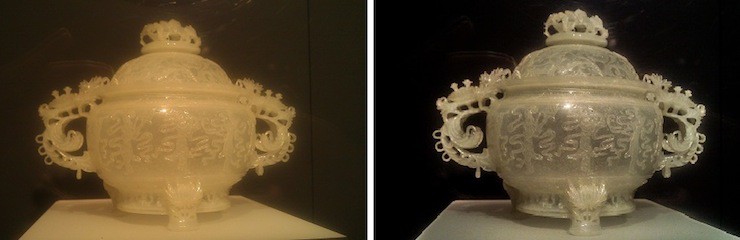

Mostly I don’t do anything very radical to my pictures. 99 percent of the time, what I’m trying to do is make the image look more like what my eye saw; even when I’m trying my best with the camera settings, things often end up just a little bit “off.” Too dim, too bright, too washed-out. The before-and-after below is a fairly heavy edit for me, but it’ll give you a sense of what I mean about making the picture look like the reality:

I took that image through museum glass with my phone’s camera, which means it didn’t start out very good. Through the magic of Lightroom, however, I was able to save it—to transform it back into something more like itself.

Not that there’s anything wrong with going whole hog on the editing! I wanted a shot of this one floor carving in Okinawa, but the light was such that there was no way for me to get a straight overhead view without casting a major shadow over part of it. After a massive amount of cropping and tilting and futzing with the colors, here’s the before and after:

Or take the case of some of my early print photos. When I went to have them scanned, I discovered that a lot of them had begun to yellow around the edges. Mostly I didn’t care, because they weren’t good shots to begin with, but in the few cases where the composition was worth it, I dropped a sepia filter over the whole thing and then fuzzed the edges out to black, making them look very old-fashioned (and coincidentally hiding the yellow).

But development can only get you so far … which is where a better camera comes in.

This is almost where my story ends. I did upgrade the V-Lux 2 to a V-Lux Typ 114, a newer model from the same line; it is vastly superior to its outdated cousin (which, remember, was a hand-me-down when I got it). I’ve resisted getting a system camera, though, despite knowing that having a wide-angle lens and a telephoto and so forth would advance my skills yet again. Quite frankly, I don’t want to carry that much weight around with me when I’m traveling. Plus, my husband is already remarkably patient with the amount of time I spend adjusting camera settings, taking the same shot three or four times because it still hasn’t come out quite right. I don’t want to ask him to wait even longer while I change out lenses.

Still, that doesn’t mean my photography can’t still improve. In many ways, I’ve gone back to the basics: framing and composition. You see, over the years, photography has changed the way I see.

Take this picture, for example:

That’s from Notre Dame in Paris. Had I gone there before I got serious about my photography, I would have been impressed; I would have taken pictures of the nave and the monuments and other such obvious things. But I wouldn’t have stopped to look at the round metal stands that hold dozens of tiny votive candles, some of them lit, some burned out, with other islands of light floating in the dimness beyond. I might have photographed the great door through which I entered, but I wouldn’t have snapped a close-up shot of the door knocker and the intricate ironwork that covers the boards. I would have admired the stained glass, but not shifted around until I could get a perfect silhouette of a statue in prayer, black against the color behind him.

I see more, now that I’m looking with a photographer’s eye. Details make for good images, so now I actively seek them out. And not just when I’m traveling: I’ll stop on my way home from the post office to pull out my camera and capture the sight of a brilliant autumn leaf in the middle of a freshly-paved sidewalk slab.

I still am much more of a writer than a photographer. But in little more than five years, I’ve gone from learning what an f-stop is to displaying eight of my photographs at Borderlands Books in San Francisco, putting them up for sale for the first time in my life.

I consider myself a photographer now, as well as a writer. I like the way it makes me see.

Marie Brennan is the World Fantasy Award-nominated author of several fantasy series, including the Memoirs of Lady Trent, the Onyx Court, the Wilders series, and the Doppelganger duology, as well as more than forty short stories. More information can be found at her website. To purchase prints of her photographs, contact her at marie.brennan@gmail.com.

Marie Brennan is the World Fantasy Award-nominated author of several fantasy series, including the Memoirs of Lady Trent, the Onyx Court, the Wilders series, and the Doppelganger duology, as well as more than forty short stories. More information can be found at her website. To purchase prints of her photographs, contact her at marie.brennan@gmail.com.

I love taking pictures (and curating my collection – I try to avoid albums where I have 7 shots of the same thing in a slightly different angle, etc) although I”m really not that into the technical aspect (either of fiddling with camera settings, or doing anything with it afterwards). My husband is much more knowledgable about that – perhaps not to your level, but he at least knows how to use f stops and ISO levels and can do a bit with photoshop. It’s really interesting to see what the after-editing can do. I confess I have a bit of a bias too against it – like it somehow seems ‘fake’. But I also know several talented professional photographers who spend a ton of time on this; to the point that they lose money on their business because if they truly charged for their time, their prices would be a lot higher than all the amateur photographers who don’t do all of that. It’s a struggle for them.

I do think I have a good eye for shots though. I still am a bit amused that when some relatives got married, when they created their year end photo card with wedding pictures, all but one of the pictures they used were ones I took, instead of the photographer’s. And I also love to notice details like the ones you point out :)

Also, anything with Veronica Mars is awesome :)

If you don’t want to get an SLR, get a superzoom. Canon makes a good one. But if you really like fiddling with settings, get an SLR with a decent wide-angle-zoom lens. The kit lens that comes with the “prosumer” SLRs is usually Good Enough. Be advised that good lenses often cost more than the camera.

Thanks for the great post, Marie. Your work at Borderlands is very nice. I especially like the Kyoto lantern and the Palazzo Ducale black and whites. They each have a moody or mysterious feel to them that appeals to me.

I love how an interest in one art often leads to an interest in others. and how work in one can help inform, shape, or inspire another. There can be a real interplay between them. When I was young I started writing, but at some point stopped. Later I took up drawing and painting, and as before, eventually stopped. Then came photography, and once again, I stopped. But years later, when digital cameras appeared, I picked up the camera again and haven’t looked back. I created a website to show my work, but mostly to encourage myself to keep shooting. As part of this I added a blog to the site, so photography is reigniting my interest in writing. One art leads to another. And I completely agree with you, spending time behind a camera can change how we see the world. It’s a beautiful thing!

I love your photos, and I love the way that you’ve described how photography lets you see differently. I’ve had a very similar experience.

Lisamarie — Yeah, when deciding how to price the photos I’ve put up for sale, I had to base it on the cost of printing. If I took editing and all the rest of it into account . . . O_O I’d have to be a LOT more famous to even break even on that.

wiredog — I looked at Canon when I was choosing a new camera, but wound up going with the Leica because the screen is on a swivel mount, which is *hugely* useful when I need to take pictures at weird angles (and I do that a lot).

thedelfrog — All hail digital photography, which lets us have fun without the cost of printing everything! :-) Glad to hear you’re having fun with it again.

adrianne — thanks!

It’s often said that writing isn’t work, *rewriting* is work. Similarly, the difference between a picture being taken and a picture being made is in the editing.

When Ansel Adams died, they found scores of undeveloped rolls of film he’d shot. They threw them all away. Reason being that the special “Ansel Adams touch” didn’t come from just his subjects but how he manipulated them in the darkroom. If you ever get a chance, go look at Adams’ original print called “Aspens” and compare it to reproductions. Adams’ original print is luminous and ethereal; it looks magical, as if it were taken a dawn in Middle Earth. (http://www.aaronartprints.org/adams-aspensnorthernnewmexico.php) Repros look like someone snapped it in their backyard. Flat, ugly, pedestrian, no blacks, no light, no mystery.

I think you need two things in both writing and photography: you have to see what others do not, and you have to see the *potential* others do not.